Industry Leaders: IRFAN THASSIM

A: Why fish farming? The short and sweet answer is, Sri Lanka is a tiny little island in a vast Indian Ocean. Sri Lanka relied mostly on a land -based economy, whilst the oceans lay abundant, and in my opinion, underutilised. Therefore, the use of the ocean became clear. I wanted to stay away from fishing because I considered that as a finite resource and in a depleting state, I didn’t want to be part of any further depletion. So, fish farming in my opinion, was some form of a renewable production system that is located in the ocean. This was my purpose in deciding to go for fish farming.

In terms of what I had hoped to achieve when I started the venture, after 20 years in the textile industry, which is one of the key pillars of Sri Lanka’s economy, I wondered if it would keep us going for the next 50 to 100 years. My desire was to start an alternative vertical economic model such as tea, rubber, coconut, tourism and apparel. My thoughts were whether an aquaculture-based economy could be established for Sri Lanka where hundreds and possibly thousands could gain employment, especially the coastal communities which are predominantly underserved in Sri Lanka, as well as contribute to export revenue and food security for the country, region and the world. These were my primary goals in setting up Oceanpick.

Q: Was the regulatory, financing and business environment conducive at that time for the planning and implementation of barramundi aquaculture out at sea? Placing this question within context, Sri Lanka’s aquaculture sector in the early 2000s contributed less than 5% of the annual national fish production; and even then, much of it came from the small-scale sector. How did you address the inevitable challenges that arose?

A: The regulatory framework, financing and business environment for the project was not in place nor was it conducive at that time. However, my motive was very strong to build for Sri Lanka another vertical economic model. What I have realised is that when the motive is strong, the obstacles seem less important. I understood that I was going to face a lot of hurdles and I prepared myself for that.

How did I manage? Expect very little from the government stakeholder sector but work with them and take them on the journey; create what you want to do, not to sit and complain. We had to do certain things on our own, in contrast to what I have seen in other countries where their governments play a massive role, or they give subsidies and offer financial support to entrepreneurs since they are breaking new ground for the country. It is what it is. There was no thought of sitting back; somehow, we managed it. Furthermore, in the process, we helped to formulate some aquaculture policies for the government.

We worked with my partners in Scotland to understand what monitoring mechanisms need to be in place because this was about setting up the infrastructure and the framework, not just for us, but for an Industry that might follow. In terms of funds, Sri Lanka had faced a very bad experience with shrimp farming and so the finance sector was very reluctant to partner with anything that was perceived as innovative. We struggled as a young company with very limited resources to raise financing, be it through the private equity side or whether debt financing – it all came with a massive battle. As a result, so much energy was taken up for administrative work that it took away a lot of the productive time we could have had to focus on farming and innovation. Having said this, I think I would still happily do as many things as I can in Sri Lanka for the benefit of future generations that will be living in this country, just so that they can enjoy better access to industries.

To the question on how I addressed the inevitable challenges, I think in any country you need the mindset to succeed. In other words, to achieve anything, the right mindset is necessary because you are pioneering, you are innovating, you don’t have the necessary framework, you don’t have the necessary staff that you can hire, there is a lot of adversity, and all odds are stacked against you. If you want to get into an industry in that space, you’d better be ready to weather the storm.

Oceanpick opened a completely new market and broke new ground. We have created a good reputation for oceanic-produced premium quality Sri Lankan products for the global marketplace. We have set ourselves as a benchmark. From the beginning, I was very keen to set the record straight with the global network that we are very ethical and compliant with international standards. It is not just for us as Oceanpick but for Sri Lanka as a country which should be seen as a credible, ethical, and forward-thinking player in the global aquaculture industry. I’m hoping that anyone else who comes along will follow the same high standard we try to set ourselves.

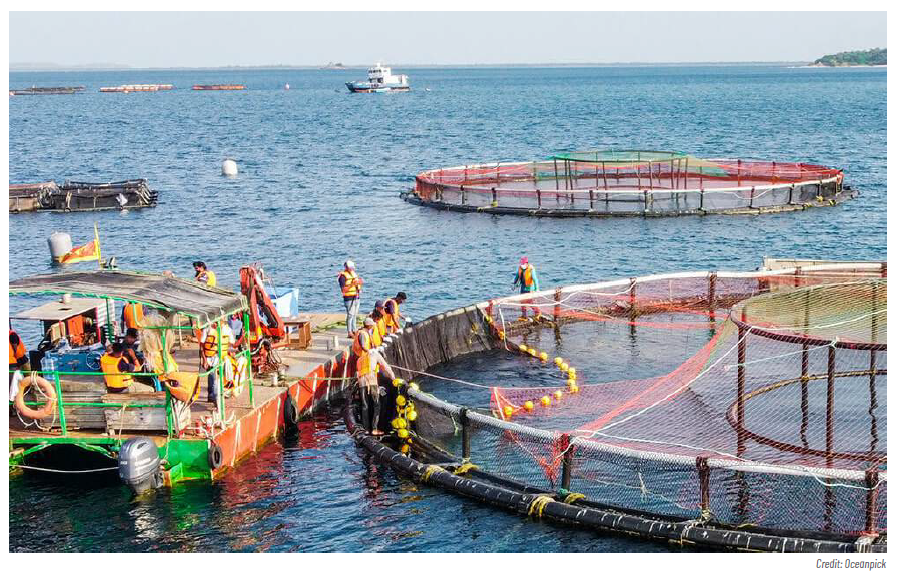

Q: It’s been about 12 years since the first Oceanpick cages were set up. Could you walk us through the production process from the hatchery stage, right up to packaging for sale? For example: fingerlings produced in your own hatchery, the production cycle and cost, feeds, weight at harvest, processing and packaging, as well as manpower and technological requirements.

A: Farming at Oceanpick is basically made up of multiple stages. As you rightly pointed out, you start with a team of knowledgeable experts, then you have your broodstock, and your protocols to be able to produce eggs, larvae, fry and fingerlings. Then you have your protocols to onward transfer them to the ocean, and you have several stages in the ocean as well. It’s too wide-ranging to explain here but in summary, you have a broodstock to egg to distributor flow. We have all that carved out into a process which happens day in and day out.

There are team members that are nurturing the broodstock, some feeding the larvae and others who are operating the harvest, nets in the cages, maintenance of the boats, and other tasks. There is a whole process intact. We are very fortunate to have a wonderful team and a wonderful set of customers from around the world who work with us, while we work on products that suit their markets – the cuts, the sizing, the formats and packaging. We have a fulfillment team that focuses on customer orders.

The hatchery was a later addition. We used to rely on an outside supply of fingerlings, but that didn’t work too well for us. In 2018–2019, we got to a point where we had to make a decision based on the available data that we had of outside-sourced fingerlings and their survival rate, among other factors. We had to attempt to try and change course. With that in mind, we set up a hatchery. We had fantastic support from the likes of the late French aquaculture pioneer Alain Michel, who helped us with setting up the hatchery. I’m very happy to say that we named our hatchery after him. He was such a great influence and impact on Oceanpick and the general aquaculture world. He was an unsung hero. We still celebrate him every day.

Our journey of 12 years includes perfecting the production system, onboarding customers, attending seafood shows and product development. Other than that, if you look at our case in particular and Sri Lanka in general, we had to overcome adversities such as the 2019 Easter attacks. At the time our business was heavily reliant on the HORECA and food service sectors in Sri Lanka, which collapsed after the Easter attack and that nearly saw the end of Oceanpick. As we were rising from the 2019 issues, 2020 brought COVID-19 which impacted everyone and all businesses. Then as we were overcoming that period, we had an economic crisis in 2022. It has been pretty challenging for us and yet, we are still pioneering our own thing. It was phenomenal to try and manage it, but I can tell you, it makes life a whole lot easier when you have an awesome team, when you have awesome customers, and when you have an awesome set of supply partners who work together, it makes life easier. I also had investor partners who supported and encouraged me to hang in there and keep going. So here we are.

Q: To our knowledge, Oceanpick is the only offshore fish farming company in South Asia which has been awarded the Best Aquaculture Practices (BAP) and Aquaculture Stewardship Council (ASC) certification. This has undoubtedly helped to facilitate Oceanpick’s access to international markets, including those with stringent regulations such as the European Union. What are the company’s biggest international markets and can you elaborate on the volumes sold as well as preferred product forms in each market?

We were a fairly under-resourced facility during the 2018/2019 period, and we were struggling on many aspects of the business but we found some resources to allocate for BAP certification and after that, we never looked back. We obtained ASC and Sedex Members Ethical Trade Audit (SMETA) credentials, and we are an ESG-focused organisation. This flows from top to bottom – everyone in our organisation understands the ethos is based on that.

Now, how does that impact in the marketplace?

Today’s marketplace is generally trending towards ESG compliance. ESG compliance is not even something to boast about anymore. I think if you are not compliant, you are not in the game. The certification, logos on the packaging and so on, are the outward visible elements and are the least important to me. What is important to me is the core belief system in the company. What does the company do when not under scrutiny?

I consistently encourage my team and other global producers to adhere to the core belief system of the company as I think the planet and the future wellbeing of the soil, oceans and the air is our collective responsibility.

If delivering a return on investment means harming the environment, then that so-called “return” is not truly a return. Profit that comes at the cost of the planet cannot – and should not – be classified as profit. It might benefit a narrow group of shareholders in the short term, but it does so at the expense of generations to come. Therefore, we have to find the right balance.

I can tell you with pride that the product that comes out of the Trincomalee ocean in the form of our Round Island Barramundi has been remarkably received by markets in terms of the flavour profile, texture and appearance of the fillets. One needs to only add salt, lime and pepper, and pan fry for a couple of minutes – that’s it. You don’t need to mask it with anything, no sauces, nothing required, keep it plain and simple. And it’s wholesome. It’s got the omegas, it’s got a whole bunch of nutrients which are good for the mind and body, and it’s also good for the planet.

Q: Linked to the previous question, what is your international market forecast for Oceanpick by the year 2030, and how do you intend to get there?

A: In terms of volumes, it’s a moving target, but our ambition is clear. We aim to become a global leader – to place barramundi among the top three to four whitefish species in the world. Again, this is what we feel very strongly. Our selling points include the flavour profile and the sustainability angle, the provenance of Trincomalee, the Sri Lankan story, as well as the beauty and the unspoiled nature of Sri Lankan landscape. We are not a country that is highly industrialised, we’ve got a lot of our old charm built in. All these salient points get flushed into the product and the people that produce the product, and that’s what we hope the world will recognise.

By 2030 we hope to be a global leader for one of the best whitefish species in the world – to stand at the apex of ethically produced, sustainable aquaculture. In terms of output, we may hit 5 000 – 10 000 tonnes. For now, barramundi is our primary focus but we do have the potential in future, given the infrastructure and the conditions that we have, to maybe add on other species. We will also continue to focus on bringing value to customers – for example, food that consumers can prepare quickly at home and eat without a lot of preparation. It will be fast, but not junk food. By 2023, we will probably have added more variety to the barramundi product offerings other than just the fresh and frozen.

Oceanpick has already started on its journey of producing convenient foods. To realise this ambition, we have multiple entrepreneurial teams that are trying different offerings all the time. We keep exploring how we could add value to our consumers and to our distributor partners. We constantly work and align ourselves with what consumers and distributors might expect from a global leader producer.

Q: Moving on to the domestic market, could you give readers an idea of the volume and value of annual sales of Asian seabass? What are the preferred product forms, who buys the fish, and how does it compare in the consumers’ minds and wallets with other fish species in the market?

A: At the inception of our journey, 90% of our supply served the domestic market. Oceanpick product is now on the menus of restaurants and the food service businesses which were once primarily reliant on wildcaught, seasonal barramundi. We offered uninterrupted supply at stable pricing; now, other producers (including from the small-scale sector) can also leverage and piggyback on us in a more formalised manner. We value the current landscape and the positive ripple effects it’s having across the industry. Today, our share of the domestic market is less than 5% – a shift that reflects our export-led strategy and our commitment to supporting broader industry development within Sri Lanka.

We recognise and respect the role of smallholder producers in Sri Lanka’s aquaculture landscape. We want them to thrive and don’t necessarily put a lot of pressure on the domestic market where they can enjoy their market share. Instead, we focus on exporting our products, allowing smallholders the space to thrive locally, particularly in the food service sector and other domestic channels. Our goal is to complement, not compete. We also believe that the global networks and infrastructure we’ve built shouldn’t be captive to us alone and should be available to others as well. We’re committed to opening up access to those who are ready, especially smallholder producers, so that they, too, can participate in international trade.

At the same time, our goal always is to be able to supply the population in Sri Lanka from a food security standpoint. For instance, if we are called upon to produce because of something like the pandemic and there are supply shortages of food in the country, we are always mindful that we will be able to fulfill that task to the best of our ability.

Q: Stepping away from a purely business lens, what is Oceanpick’s involvement with regard to promoting economic development in local communities, and supporting climate-resilient livelihoods for coastal communities in Sri Lanka?

A: This is a very personal and cherished area for me. Every morning, every day of my life, I keep thinking what I can do in my lifetime – what I can do for Trincomalee, which is deserving, just like the rest of Sri Lanka, which is in need of some intervention. It’s a place close to my heart, and like many parts of Sri Lanka, it deserves meaningful and lasting intervention.

Our work in Trincomalee isn’t just about business. It’s about purpose – about contributing to a region with immense natural beauty and potential, and ensuring it becomes a symbol of sustainable progress. What we’re building here isn’t just for today – it’s for generations to come. This is my personal philosophy in life. I think there are those who need intervention and those (like me) who have the ability to do interventions. I am very passionate about seeing how we can support Trincomalee. Personally, I also would love to do something for my hometown, Hambantuta, where unfortunately I couldn’t start my farm.

Everything we do tends to revolve around profit – and yes, profit is important. It allows for continuity, for reinvestment, and for the ability to scale impact. But when profit becomes the sole motive, it creates a tension. Because then, you’re not always doing the right thing – you’re just doing what pays.

I’m not a climate expert. I’m an accountant by training, and I came from the textile industry. But I can feel what’s happening around us. Temperatures are rising. Landscapes are changing. Something isn’t right. And while it’s not my job to quantify the harm, it is my job to understand what role I can play in this moment.

One of the statements I made at the beginning is that I want to be careful of dealing with anything that is finite. I’m on a private mission to ensure that I pass on some values and what I have learned. For example, talking to my children about the planet and sustainability, and impressing upon my office team about the importance of teaching their own children about saving the planet in whatever form they can. It is difficult to address the current generation and I don’t know whether we can adequately reverse this now. My focus would be to skip this generation and take on the next.

My team also constantly engages with local fishing communities (in particular, the children) and organises fun activities. I hope that in the near future, these children can be taken on plastic collecting rounds on the beaches to impress upon them the importance of not polluting the beaches and their environment. In Trincomalee, we work closely with a few nearby villages near our farming sites—not because of any specific framework or ESG matrix, but because it feels like the right thing to do. We act from the heart. When social impact is driven by a need for recognition, the intention risks becoming transactional. The only “return” I seek is that these communities thrive – that they gain access to the same tools we often take for granted: education, healthcare and opportunity. If we can change one town, one household, one child, it matters – one transformed community can inspire others.

We’re working on small, quiet initiatives like identifying promising children and supporting them with resources, mentorship, and tracking their progress. Who knows, maybe one of them will end up at NASA, or become a global leader. The ultimate dream is that they return and uplift their own communities.

Q: And lastly, if you were facing a room full of would-be commercial fish farmers in Sri Lanka, what would you say to them?

A: I will tell them two things:

• Be fiercely compliant. Example, if there’s a mangrove where birds forage – maybe the last 10 of their kind – and you’re tempted to clear it for profit: don’t do it. That’s not the kind of growth we want. True progress is built on responsibility. If every farmer and every producer upholds strong compliance, we can build a reputation for Sri Lanka that the world respects – one rooted in ethics and sustainability.

• Secondly, be fiercely competitive. Too often, I’ve seen a mindset that suggests being Sri Lankan means we’re somehow entitled to be less competitive. That we should be paid more just because our product is “special.” My view? If your product commands a premium – fantastic. But don’t walk away from the table if you can be competitive.

These are the pillars I would love to see our industries – and especially our next generation – build on: compliance and competitiveness; values and performance; heart and hustle.