Article II 6/2024 - HOW HARVEST STRATEGIES ARE REVOLUTIONISING FISHERIES MANAGEMENT

First, let’s look at the most pressing threat to ocean biodiversity: overfishing. The number of fisheries experiencing too much fishing continues to grow, putting fish populations, food security, livelihoods and ecosystem health at risk.

According to the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture (SOFIA) 2024 report, from 1974 to 2021 the number of fish populations worldwide within biologically sustainable levels decreased from 90% to 62%. Numerous factors are driving this decline, starting with the fact that throughout most of human history, people thought they didn’t need to worry about supply and that the ocean was filled with limitless fish that could be taken without threatening the size or health of fish populations.

But that changed in the last half century due to a confluence of factors, including a growing demand around the world for animal protein, the advent of large industrial fleets and ever-advancing fishing technology that allows vessels to find, access and harvest enormous volumes of marine life. Some modern vessels can stay at sea for more than a year, supported by carrier ships that collect and process catch, and resupply food and fuel. The result is that some fishers make far fewer trips back to port and have far less downtime from fishing than in decades past.

And even as fisheries scientists and some managers recognise this reality and have called for reasonable constraints on fishing, the commercial industry continues to question legitimate science and lobby hard – and often successfully – for liberal catch limits and other policies that help maximise the industry’s short-term profits, regardless of what these policies might mean for ocean biodiversity and long-term fisheries sustainability.

But the reality is that today, the tools exist to prevent future severe declines in fish populations altogether and reverse some of the mistakes from the past. That’s because along with advancements in fishing technologies and tactics has come significant progress in fisheries science and management. Specifically, adoption of novel, sciencebased management approaches known as harvest strategies has proved successful in valuable, high-volume fisheries and helps keep fish populations sustainable without overly restrictive catch limits.

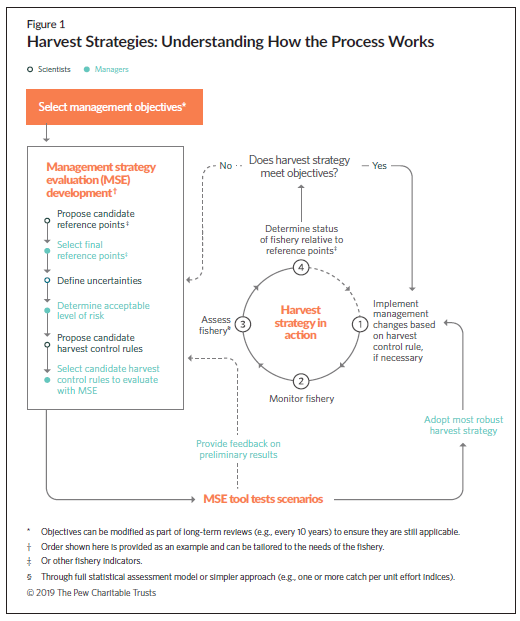

Harvest strategies, also known as management procedures, stand in contrast to traditional fisheries management, which often considers only the short-term status of a target population – say, southern bluefin tuna – when setting quotas and other measures. Instead, harvest strategies use scientific models to take the guesswork out of determining catch and effort limits and help managers set fishing limits for years at a time, reducing the need for contentious, yearly negotiations. When implementing a harvest strategy, managers and fishing companies agree in advance (“pre-agree,” in the parlance of harvest strategies) to raise or lower the catch limits if certain benchmarks in the fish’s population are surpassed.

For example, by 2011, the population of southern bluefin tuna had declined to only 5% of its historic size, spurring managers at the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT) to take action to stop the bleeding. So, the Commission developed a landmark harvest strategy, known as the Bali Procedure, that gave the CCSBT 25 years to quadruple the abundance of southern bluefin to 20% of its unfished size – a goal it achieved in less than 10 years while increasing the catch limit by 87%. At the same time, the fishing industry benefited from the increased catch and smoother financing (because of the predictability of catch year to year). By 2019, when the harvest strategy was revised, managers were able to increase their target to rebuild the southern bluefin tuna population to 30% of its unfished size.

FAO also noted that the number of principal commercial tuna species that were fished within biologically sustainable levels in 2022 was significantly higher than the global average of all capture fisheries – an improvement from earlier analyses. While FAO doesn’t distinguish between stocks that are managed by the major RFMOs and those that are not, the positive tuna numbers, along with similar positive trends in other high-volume fisheries managed by RFMOs, indicate that thoughtful management interventions, such as harvest strategies, do work.

It’s encouraging, then, that more RFMOs are adopting harvest strategies. Examples include one for North Pacific albacore adopted in 2023 by the Western and Central Pacific Fisheries Commission and the Inter-American Tropical Tuna Commission, which jointly manage the population, and another for Indian Ocean bigeye tuna adopted by the Indian Ocean Tuna Commission in 2022.

To build on this progress, more international fishery management bodies, along with domestic management authorities, should adopt and implement harvest strategies. And because of the scalable and flexible nature of harvest strategies, they work equally well with fisheries that are large or small, complex or simple, heavily fished or not.

What makes a successful harvest strategy?

Because these objectives usually include at least some contradictory goals – for example, maximising catch as well as the number of fish left in the water – managers must craft rules that balance the competing objectives as well as possible.

As such, all harvest strategies should include these basic elements:

• Management objectives that set the vision for the fish population

and fishery;

• A monitoring program to collect data;

• Indicators of the fishery’s status and population health;

• A method to assess those indicators using collected data, such as

an assessment model or a simpler approach using, for example,

catch per unit effort (such as the number of fishing days or number

of hooks used); and

• A harvest control rule (HCR) that sets fishing opportunities, such as

catch or effort limits, depending on stock status.

The many benefits of harvest strategies

Harvest strategies and MSE jointly have another significant benefit: They can help fisheries managers implement the ecosystem approach to overseeing fisheries, something they’ve been tasked to do since the 1995 United Nations Fish Stocks Agreement but have mostly failed to accomplish.

Ecosystem-based fisheries management accounts for the effects of fishing on a range of species – not just the one targeted – and their habitats. It also incorporates the effects of changes in the environment, such as shifts in microscopic plankton prey levels or temperature, on fish biomass, geographic range, or fisheries. This approach requires managers to consider interactions among species – for instance, how fishing of one species will potentially deplete the food available for another, or how fishers targeting one species may accidentally catch other species.

Ecosystem-based fisheries management decisions must be driven by evidence-based, ecological objectives including safeguarding the integrity of food webs, ensuring wider ecosystem functioning and maintaining resilience to environmental stressors like climate change, rather than focusing only on the aim of catching as much of one stock as possible.

Harvest strategies are a perfect fit for meeting these objectives. The case of forage fishes provides a prime example: These species – anchovies, herring, sandeels, menhaden and more – form an important part of marine food webs by connecting their prey (microscopic plankton) to their predators, including seabirds, whales and other fishes.

So although the data on, say, sandeels alone might suggest a catch limit set at the maximum sustainable yield, an ecosystem-based evaluation of the fishery would offer a lower limit to ensure that the sandeel population stays healthy enough to continue as food for bluefin tuna and puffins. This is critical not only from a strict biodiversity standpoint but also because bluefin are a hugely valuable species economically and puffins are a major tourist draw in many northern latitudes.

Harvest strategies can also help bring stability and predictability to each level of the seafood supply chain. For example, the harvest strategy for southern bluefin tuna ensured fishing operations a consistent, predictable catch limit – allowing the operators to make longer-term business decisions, and also receive more favourable financial terms and easier access to credit from banks that no longer had to worry about the risk associated with the ups and downs of annual negotiations of catch limits.

Similarly, operators at sardine and anchovy processing plants in Albania and Montenegro have indicated to scientists at the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM) that they prefer stability over maximum volume in the amount of product coming to their facilities, because this stability and predictability helps them make more reliable long-term business decisions.

These two examples highlight another benefit of the transition to harvest strategies: increased opportunities for outreach to stakeholders in industry, supply chain management, the conservation community and other sectors. In traditional fisheries management systems, catch limits and other rules are often negotiated by a handful of bureaucrats in a closed room or listening to only the most powerful representatives of the fishing industry. In contrast, from the development of management objectives to the choice of a final harvest control rule, harvest strategies benefit from – and rely on – participation by these various stakeholders.

Where are harvest strategies working?

And an additional few dozen domestic fisheries are managed via harvest strategies.

Some of these victories were hard fought, including the International Commission for the Conservation of Atlantic Tunas’ (ICCAT’s) 2022 adoption of a harvest strategy for Atlantic bluefin tuna – a move that has helped ensure that the once-decimated species should not again become overfished for the next 30 years. Managers can achieve that outcome, as long as they commit to faithfully following the adopted rule.

And in response to serious overfishing of Pacific saury – a small, economically valuable fish that plays an important cultural role in Japan – the North Pacific Fisheries Commission is developing a harvest strategy, with an interim HCR already in effect that should end overfishing and begin the population’s recovery.

With harvest strategy successes continuing to mount, more RFMOs, governments and other bodies should develop and adopt the approach. Specifically, harvest strategies would benefit shrimps, lobsters, and other shellfish, and even short-lived, highly productive squids. Managers should also consider harvest strategies for more prey species, such as mackerel and herring – not just to maximise catch but to protect marine ecosystems and food webs.

The sardine and anchovy fisheries in the Adriatic Sea are the next international opportunity for adoption (early November at GFCM), followed by north Atlantic swordfish and western Atlantic skipjack tuna (late November at ICCAT). From there, the international community should double, triple, and quadruple down on harvest strategy adoption and implementation.

Barriers to harvest strategy adoption – and how to overcome them

- Education and capacity-building. Many managers, scientists, fishers and other stakeholders are reluctant to move on from the familiar realm of traditional fisheries management. They will require education to learn how harvest strategies can be more efficient and effective than their current approach.

- Development timelines. In many cases, harvest strategy processes have lacked clear workplans, the necessary funding and staff capacity, and/or a forum for the iterative exchange among scientists, managers and other stakeholders that is a hallmark of the approach – leading in turn to protracted development timelines. On the flip side: Because the Northwest Atlantic Fisheries Organization tackled each of these potential roadblocks when drafting a Greenland halibut harvest strategy, the strategy went from concept to implementation in a little over a year.

- The limits of harvest strategies. For all their advantages, harvest strategies can’t solve every fisheries management challenge. For example, allocation of fishing opportunities – including allocation of harvest strategy-based catch limits as quotas to individual States – will always require political negotiation in real time. So managers must find a way to equitably allocate these fishing opportunities in a straightforward manner that doesn’t threaten the development, adoption or implementation of harvest strategies.

Conclusion

But it’s vital that fishery managers faithfully follow a harvest strategy once it’s implemented. If, instead, managers happily raise catch limits when the strategy allows but decline to decrease limits when required by the strategy, the system will fail, leaving affected fisheries at risk of depletion and eventual collapse.

In the end, the future of global fisheries rests with those who set the rules. Science and experience are showing the world the right way to do that; it’s now up to governments, RFMOs and seafood supply chain companies to support harvest strategies and keep all of the world’s fisheries sustainable for generations to come.