Article II 1/2025 - WHY GENDER MATTERS IN FISH LOSS AND WASTE REDUCTION

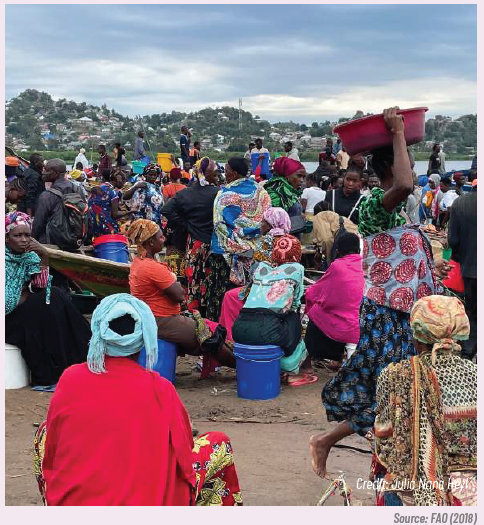

A key factor in addressing fish loss and waste is recognising the oftenoverlooked role of women in fisheries. Women are integral to the fisheries and aquaculture value chain, especially in post-harvest activities such as processing, storage, and marketing. In 2020, women made up 21% of the 58.5 million people employed in the primary fisheries and aquaculture sector. When considering the entire aquatic value chain, including preand post-harvest stages, women account for nearly half of the workforce. When considering the available data for the processing sector only, the numbers are even more impressive: women accounted for just over 50 percent of full-time employment and 71 percent of part-time engagement (FAO, 2022b)3.

However, women are disproportionately represented in the informal, low-paid, and unstable segments of the workforce (FAO, 2022b). Despite their critical role in generating income and ensuring food security for households and communities, their work is often invisible, undervalued, and they face significant barriers to full participation and equal benefit from the fisheries and aquaculture sector.

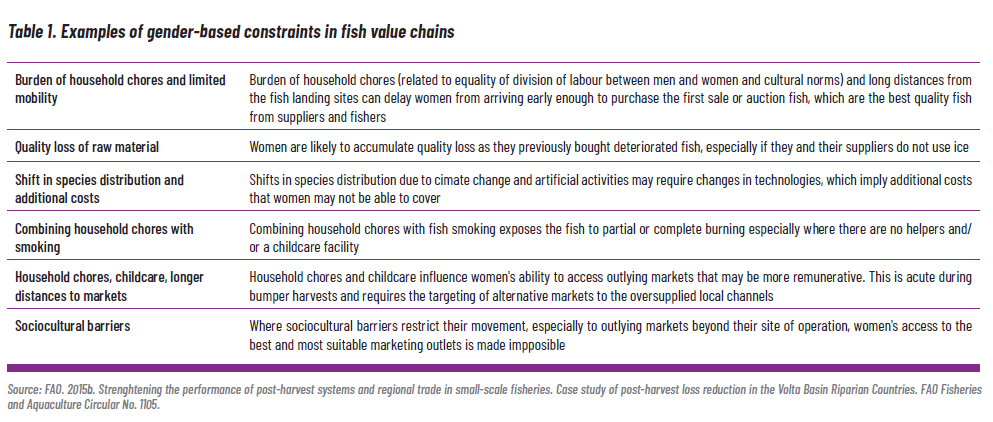

Women often face gender-based constraints that prevent them from fully exploring and benefiting from their roles in the sector (FAO, 2022b). This marginalisation can hinder efforts to improve the efficiency and sustainability of aquatic and fish value chains; and resulting inefficiencies will increase the losses suffered in the sector (FAO, 2018). By integrating a gender-sensitive approach into fish loss and waste assessment and reduction strategies, we can address existing inefficiencies, empower women, and build more resilient food systems. This approach will not only help reduce global fish loss but also enhance the livelihoods of millions of people who rely on fisheries for their income and sustenance.

1 FAO. 2022a. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2022. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

2 FAO. 2020. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2020: Sustainability in Action. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

3 FAO. 2022b. The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022. Towards Blue Transformation. Rome, FAO.

The link between gender equality and losses along value chains

4 FAO. 2019. The State of Food and Agriculture 2019: Moving Forward on Food Loss and Waste. Rome, FAO.

5 FAO. 2018. Gender and food loss in sustainable food value chains – A guiding note. Rome.

6 Randrianantoandro, A., Safa Barraza, A., Ward, A. (2022): Gender and food loss in sustainable fish value chains in Africa, Rome.

Access to productive resources

Productive resources are necessary to conduct activities along the entire food value chain and can be grouped into three categories:

- Assets: In the context of fisheries, assets include the ecological assets (i.e., marine and aquaculture resources in the contexts considered), the equipment and technologies used along the fish value chain (from fishing to processing and marketing activities), and the capital used in activities related to fisheries.

- Agricultural services: In the context of fisheries, these services include those provided in landing sites, cold storage infrastructure, markets (including market information, infrastructure, and organisations), transport equipment and infrastructure, electricity, processing units, and extension services including training and insurance when available.

- Financial services: In fisheries, these refer to financial services involved in fish value chains.

Power and agency

These concepts refer respectively to the control over resources and profits and the ability to make autonomous decisions on their use. Genderbased constraints in this area affect women’s and men’s capabilities, selfconfidence, and decision-making power.

Gender-based constraints can be defined as “restrictions on men’s or women’s access to resources or opportunities that are based on their gender roles or responsibilities” (USAID, 2009)8. Identifying and analysing gender-based constraints enables the value chain practitioner to understand and address the root causes underlying value chain inefficiencies related to gender inequalities and discrimination, thus enhancing the sustainability of interventions (FAO, 2016). The inequalities that lead to gender-based constraints can be grouped into two dimensions: (i) access to productive resources (assets, agricultural services and financial services); and (ii) power and agency which refers respectively to the control over resources and profits, and the ability to make autonomous decisions on their use. Gender-based constraints in this area affect women’s and men’s capabilities, self-confidence and decision-making power (FAO, 2018).

7 FAO. 2016. Developing gender-sensitive value chains. A guiding framework. Rome. 8 USAID (2009). Promoting Gender Equitable Opportunities in Agricultural Value Chains. Washington, DC.

8 USAID (2009). Promoting Gender Equitable Opportunities in Agricultural Value Chains. Washington, DC.

Gender in loss assessments and solutions development

- Create a gender-sensitive map of the aquatic value chain, identifying actors, linkages, and gender distribution;

- Identify stages with high food losses and key actors involved; and

- Assess the constraints and opportunities that affect women’s and men’s participation.

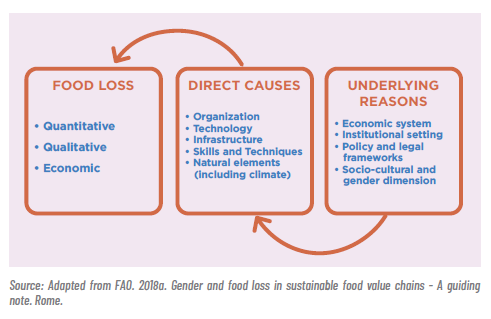

The different productive and social roles of men and women affect their access to, and control over assets, knowledge and services and their participation in productive activities and decision-making. This impacts the efficiency of the food value chain and hence is an underlying reason for food loss.

Women and men have different needs, constraints and preferences when carrying out their activities along the value chain. These gender concerns are particularly relevant in determining the response of a specific food value chain to food loss reduction policies and interventions and consequently determine their effectiveness and impact.

Institutionalising and professionalising women’s groups and cooperatives is crucial for reducing losses in aquatic value chains by fostering collaboration and knowledge-sharing. These groups provide women with a platform to access training on best practices in fish handling, preservation, and storage, which can improve the quality and shelf life of fish products. By pooling resources and negotiating collectively, women can also access better market prices and reduce post-harvest losses. Additionally, membership in organisations can strengthen women’s bargaining power, promote access to credit, and facilitate networking, all of which contribute to greater economic resilience and sustainability in the fish value chain.

Introducing technologies that are affordable and user-friendly (such as fish preservation tools) can reduce losses by improving efficiency, extending shelf life, and enhancing product quality. The acceptability and uptake of these solutions are further strengthened when they are grounded in local knowledge and traditional practices, ensuring they resonate with women’s cultural, economic, and practical realities in the sector.

Moreover, the provision of appropriate infrastructure, such as cold storage facilities or improved processing equipment, should go hand-inhand with comprehensive maintenance and management plans to ensure their continued acceptance and effective use. These plans not only help sustain the functionality of the facilities but also empower women by involving them in decision-making processes regarding the upkeep and operation of the infrastructure. By ensuring that the infrastructure is well-maintained and aligned with the evolving needs of the community, these solutions stay relevant, fostering long-term commitment and enhancing the resilience of women in the fish value chain.

The positive impact of any proposed solution is likely to be even greater when it acknowledges how gender inequalities can manifest on a personal level, often through low self-confidence and limited aspirations. Approaches that incorporate mechanisms to build self-worth and unlock confidence can strengthen women’s agency, enhance self-efficacy, and elevate their aspirations. This, in turn, fosters greater adoption of new skills and techniques, drives higher efficiency, and ultimately reduces losses and waste in the value chain.